January 30, 2015. Controversy over EPA’s proposed carbon reduction rule (see an earlier post) has again focused attention on the climate change debate. This post will look at global temperature trends as reported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Aeronautic and Space Administration (NASA).

The most recent temperature data. In 2014, the average combined land and sea surface temperature on Earth reached the highest level since modern record-keeping began in the 1880s. The latest temperature data can be found in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) 2014 Global Climate Report here. Similar results reported by NASA can be found here. Although NOAA and NASA use somewhat different baselines and methods, the two agencies reached very similar results. NASA calculated an increase of 1.4 ° (F) over the historical baseline; NOAA found an increase of 1.24° (F). Both found that higher ocean temperatures made a slightly greater contribution to the total increase than land surface temperatures.

The chart below has been adapted from a NOAA Chart showing the ten warmest years on record based on the global average temperature. All of those years, with the exception of one, have occurred since 2000. The third column shows the increase in temperature by reference to the historical average (1880-2014).

| Rank (1=Warmest) | Year | Increase (Fº) |

| 1 | 2014 | +1.24 |

| 2 (Tie) | 2010/2005 | + 1.17 |

| 4 | 1998 | +1.13 |

| 5 (Tie) | 2013/2003 | +1.12 |

| 7 | 2002 | +1.10 |

| 8 | 2006 | +1.08 |

| 9 (Tie) | 2009/2007 | +1.06 |

Some temperature fluctuation from year to year can be accounted for by El Nino (warming) and La Nina (cooling) trends in the Pacific Ocean, but the 2014 high occurred under neutral El Nino conditions. Find the original NOAA chart and other information about NOAA’s 2014 temperature analysis here.

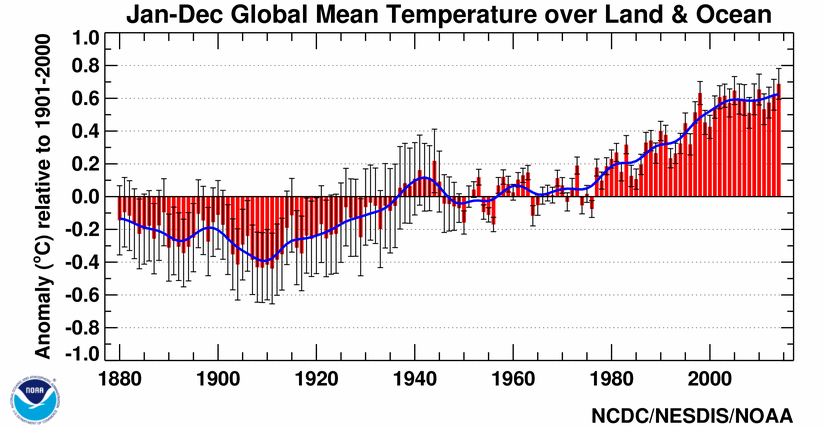

NOAA also provides a bar chart showing the trend in global temperature over the entire period

Comparison to past temperature variation on Earth. Scientists have estimated average global temperature during past warming and cooling periods based on a variety of natural records — glacial ice, tree rings, geological formations, and fossils. There have been periods in the past when Earth’s average temperature was much higher than it is now. But once Earth cooled down from a hot rock to a planet capable of supporting life, the warming event that followed the last ice age occurred very slowly. See NOAA’s introduction to climate history here. The overviews of historical climate studies provided by NOAA and by NASA’s Climate Observatory put context around recent temperature increases:

♦ Earth’s average temperature varies from year to year in response to many influences, but in recent decades, the cooler years have represented “noise” in an overall upward trend.

♦ Earth’s climate has been relatively stable for much of the history of human civilization (the past 10,000 years).

♦ The last significant warming period (which began around 11,000 years ago) led to an increase in the Earth’s average surface temperature of between 7° – 12° F. That warming occurred very gradually over a period of about 5,000 years and then another cooling trend began.

♦ The current warming trend began in the 20th century and temperature increases are happening 10 times times faster than the last ice age warming period. (NASA).

For more detail on climate history, both the NASA and NOAA sites provide links to the scientific studies used as references.

Do these increases in global temperature matter? An increase of 1.4° F over the average global surface temperature seems — and is — small, but even small increases can affect patterns of plant and animal life. In 2012, the U.S. Department of Agriculture released an updated U.S. plant hardiness zone map. The map divides the U.S. into zones based on the average annual low temperature; going from north to south, each zone on the map represents a 10° increase in the average low temperature. By comparison to the 1990 map, the new map shows a half-zone shift (or 5° F) toward the warmer zones. USDA has been careful to say the data sets for the 1990 and 2012 maps differed in a number of ways — the new map reflects data from more locations and use of more sophisticated technology as well as additional years of data. But the shifts are consistent with the general trend in global temperature data since the 1980s and suggest that farmers and gardeners may already be seeing changes affecting plant life.

While a 1.2°- 1.4° increase in the average temperature over 30 years may already be affecting the environment, concern about rising global temperature really focuses on the future. Two of the greatest concerns:

1. The rapid pace of warming and the unknown stopping point. Earth’s last major ice age warming event took place over a period of 5,000 years and at a time before modern human civilization and reliance on large-scale agricultural production. Earth’s current warming is occurring at a much faster rate (as much as 10 times faster), increasing the risk that plant and animal life may not be able to adapt quickly enough to changing temperature regimes. While Unites States agriculture has not been harmed by the 1.2 – 1.4 ° (F) increase in recent decades, it could be much more difficult to maintain agricultural productivity in the face of continuing, rapid temperature increases. Other, warmer, parts of the globe will be much more vulnerable to agricultural disruption because of temperature increases. Temperature increases can also affect other human food sources like fisheries.

2. The chain-reaction effect of rapid warming on other parts of the human environment. The chain reaction talked about most often:

Higher global temperature ⇒ melting of land ice ⇒more rapidly rising sea levels ⇒ flooding of coastal areas.

The potential for accelerated sea level rise gets attention because of the direct risk to human populations. In 2010, 39% of the population of the U.S. lived in a shoreline county; more than half of the population lived within 50 miles of an ocean shoreline. (Source: U.S. census data as reported in NOAA’s State of the Coast Report.) As a result, accelerated sea level rise could affect some of the most highly populated areas in the United States.

Note: NASA’s Vital Signs of the Planet website provides visualizations of changes in the extent of sea ice and land ice.

How reliable is the data? Temperature records date back to the 1880s and the amount and quality of the data has only gotten better. NASA describes the records used in the Goddard Institute of Space Sciences temperature calculations this way:

The GISS analysis incorporates surface temperature measurements from 6,300 weather stations, ship- and buoy-based observations of sea surface temperatures, and temperature measurements from Antarctic research stations. This raw data is analyzed using an algorithm that takes into account the varied spacing of temperature stations around the globe and urban heating effects that could skew the calculation. The result is an estimate of the global average temperature difference from a baseline period of 1951 to 1980.

Next: The role of carbon dioxide and other “greenhouse” gasses in raising global temperature.